This week's Parsha Shiur.

Rachel and Leah.

Thursday, November 30, 2006

Rebuilding the Hurva

This was on Haaretz just yesterday. It talks about the archaeology that they have found as they renovate the Hurva shul in the Old City. I always get a real thrill as we understand that as we walk through the Jewish Quarter, just a few metres under our feet is a whole undiscovered world of a Kohanim's Quarter from Bayit Sheni. In this excavation, they have even discovered finds from Bayit Rishon!

"The excavations, which began in 2003, also unearthed structures and pottery from the First Temple period, remnants of rooms from the Herodian period (Second Temple), burnt wooden logs (evidence of fire that took place after the destruction of the Second Temple), and three plastered ritual baths carved in rock from the Second Temple period. The diggers also found a small weapons arsenal, where defenders of the Jewish Quarter stashed mortar shells and grenades during the Independence War. "

The land Hurva shul was originally purchased by Rabbi Yehuda HaHassid, in the year 1700. It was meant to house living accommodations and a shul/Beit Midrash for his followers. However the buildings there were destroyed by the arabs as the Jews could not pay the loans they took to buy it. Hence the name, the Hurva. After the Talmidei HaGra made Aliya in the 1840's they built the grandest shul on the site, and it became the "Great Synagogue" of Jerusalem, it's largest and grandest shul.

And the Jordanians blew it up in 1948 leaving it as a ruin.

So here is what I would like to relate to: It is fascinating to think about the mindset of the renovation of the Rova after 1967 when we regained control of the Old City. Teddy Kollek and the other planners envisioned the Old City as an Artists Colony, an exotic place with musicians and artisans. The scenery and streets, museums and squares would also remember and recall the past. But in this context, all the shuls; the Tiferet Yisrael, and the Hurva, the grandest structures, were left in ruins. It was a very secular modern view that prevailed with Synagogues left as Historical relics of a bygone age, a museum of sorts, a lost history alongside the Cardo and the Herodian stones, consigned to ancient History.

But of course, as religious people, we see Judaism in the present. It is not a romantic past-tense but a reality of the here and now. Nowadays the Jewish Quarter is predominantly populated by the religious. Why did the chilonim move out. Well - the difficulties of living in the Old City – difficult access, close proximity to many Arabs, endless tourists – have kept away the artists. But or the religious, the notion of the proximity to Makom Hamikdash speaks with resounding power. And so, the shuls are being rebuilt and an ancient glory is being restored. The wrongs of History are being pput right!

Wednesday, November 22, 2006

Parashat Toldot: Was Yitzchak Poor?

There is a lovely machloket (disagreement) between Ibn Ezra and the Ramban regarding Yitzchak's financial status. (You can find the discussion in ch.25 v.34).

The Ibn Ezra claims that Yitzchak was poor. He says:

"The proof is that Yitzchak loved Esav because he provided his basic needs. If food was plentiful in his father's home, then why would he have sold his birthright for soup? And if his father ate all sorts of delicacies, then why did he ask (Esav) to bring him fresh meat? And why did Yaakov not have elegant clothing? And why did his mother send him penniless when went away, such that he asks God for "bread to eat and clothes to wear (28:20)"?

Some will ask; but Abraham was wealthy and it tells us that Avraham gave his inheritance to Yiztchak (25:5). In addition ch.26 talks about Isaac as a wealthy farmer. Ibn Ezra responds:

"As if one has never seen a man, wealthy in his youth who falls into poverty in his old age!"

Moreover:

"Those whose hearts are blind think that wealth is a great attribute of the righteous. Let teh case of Elijah refute that! And they continue to question: Why would God let Yitzchak be lacking in material wealth? Maybe they can answer why God allowed him to lose his eyesight!"

One senses that Ibn Ezra is "worked up" here. Ibn Ezra lead a particularly difficult life with many upheavals and travels. He certainly was not wealthy, and maybe – who knows – he identified with Yitzchak here. At the very least, he felt that (if I may quote Tevye…) it is no shame to be poor!

(The irony here is that of course, all the blessings of chapter 27 do invoke this worldly material blessings:

The agricultural – the dew of the heavens the fat of the land; abundant grain and wine.

Power – Nations will be subservient to you; other People's will bow to you! - 27:28-9)

RAMBAN

The Ramban has a very different perspective:

"The text informs us that after his father's death 'God blessed Isaac his son.' (25:11) Now, where is his "blessing" if he lost all his father's wealth - 'And I will be with you, and I will bless you.' (26:3) (is there a Divine blessing) if he became rich but then became poor? If some of the righteous experience the financial legacy of the Evil (i.e. poverty), it does not occur to those whom God has blessed… all the patriarchs were like kings, and foreign heads of State would come before them and make treaties with them[1]… and if Isaac had bad luck and lost his father's wealth, how would they have said: 'We see evidently that God is with you!' (26:28)?"

The Ramban refuses to accept poverty in the case of Yitzchak or any of the Avot. God's blessing bestow material comfort, status and honour. Ramban also rejects as "laughable" the theory that Isaac had wealth (after Avraham's death) – then lost it (the birthright episode) – then gained wealth (ch.26 Yitzchak as a successful farmer) – and then lost it a second time (the Blessings episode.) "Who blinded his mind?" - he quips at Ibn Ezra!

For the Ramban, all the other details are resolved locally.

Esav sold his birthright for soup because it had no financial dimension, and his spiritually deaf personality failed to appreciate the role of the firstborn.

As for Yitzchak's love of hunted meat, the Ramban says "that dignitaries and kings delight in this delicacy over all others. And regarding Yitzchak's request to Esav in particular that he should engage in the hunt, the Ramban remarks: "Esav would pander to his father by bringing him from the hunted food … and (Yitzchak) wanted to benefit from it so that it would enhance the closeness between them."

Yaakov left home without wealth so that he could escape quickly and so that he would not become a target for attack as he travelled the highways.

And as regards Yaakov's lack of clothing, the Ramban answers that Yaakov lacked nothing! But he borrowed Esav's clothing as they had the smell of the "field," the camouflage that Yaakov needed in order to carry off the subterfuge of the Blessings.

IN SUMMARY

This is certainly a tough debate to settle. No side wins easily. But if we can return to the basic principles, it is certainly fascinating that the Ramban refuses to see a Tzaddik who is blessed by God, experiencing financial difficulties. The Ramban needs to see a correlation between the spiritual and the material. For the Ibn Ezra, the two are absolutely disconnected. A wanderer like Eliyahu who is given lodgings by a random stranger for years on end[2] can be the holiest person. There is no symmetry between the material fate of the Man of God and his spiritual status; they are two disconnected realities.

What is the connection between the material and the spiritual? We experience the spirituality of Shabbat via material pleasure? Can there also be a correlation in other ways between material luxury and spiritual heights? On the other hand, wealth can at times be a distraction, a mode that takes a person far from the world of the spirit, to the world of indulgence and pleasure. Maybe the two are at odds with each other?

Shabbat Shalom!

[1] Each of the Avot are granted enormous respect by foreign Kings: Avraham with Malkitzedek and Avimelekh. Yitzchak and Avimelekh. Yaakov and Pharaoh.

[2] The woman from Tzrafat Melachim I 17:9,19-23.

The Ibn Ezra claims that Yitzchak was poor. He says:

"The proof is that Yitzchak loved Esav because he provided his basic needs. If food was plentiful in his father's home, then why would he have sold his birthright for soup? And if his father ate all sorts of delicacies, then why did he ask (Esav) to bring him fresh meat? And why did Yaakov not have elegant clothing? And why did his mother send him penniless when went away, such that he asks God for "bread to eat and clothes to wear (28:20)"?

Some will ask; but Abraham was wealthy and it tells us that Avraham gave his inheritance to Yiztchak (25:5). In addition ch.26 talks about Isaac as a wealthy farmer. Ibn Ezra responds:

"As if one has never seen a man, wealthy in his youth who falls into poverty in his old age!"

Moreover:

"Those whose hearts are blind think that wealth is a great attribute of the righteous. Let teh case of Elijah refute that! And they continue to question: Why would God let Yitzchak be lacking in material wealth? Maybe they can answer why God allowed him to lose his eyesight!"

One senses that Ibn Ezra is "worked up" here. Ibn Ezra lead a particularly difficult life with many upheavals and travels. He certainly was not wealthy, and maybe – who knows – he identified with Yitzchak here. At the very least, he felt that (if I may quote Tevye…) it is no shame to be poor!

(The irony here is that of course, all the blessings of chapter 27 do invoke this worldly material blessings:

The agricultural – the dew of the heavens the fat of the land; abundant grain and wine.

Power – Nations will be subservient to you; other People's will bow to you! - 27:28-9)

RAMBAN

The Ramban has a very different perspective:

"The text informs us that after his father's death 'God blessed Isaac his son.' (25:11) Now, where is his "blessing" if he lost all his father's wealth - 'And I will be with you, and I will bless you.' (26:3) (is there a Divine blessing) if he became rich but then became poor? If some of the righteous experience the financial legacy of the Evil (i.e. poverty), it does not occur to those whom God has blessed… all the patriarchs were like kings, and foreign heads of State would come before them and make treaties with them[1]… and if Isaac had bad luck and lost his father's wealth, how would they have said: 'We see evidently that God is with you!' (26:28)?"

The Ramban refuses to accept poverty in the case of Yitzchak or any of the Avot. God's blessing bestow material comfort, status and honour. Ramban also rejects as "laughable" the theory that Isaac had wealth (after Avraham's death) – then lost it (the birthright episode) – then gained wealth (ch.26 Yitzchak as a successful farmer) – and then lost it a second time (the Blessings episode.) "Who blinded his mind?" - he quips at Ibn Ezra!

For the Ramban, all the other details are resolved locally.

Esav sold his birthright for soup because it had no financial dimension, and his spiritually deaf personality failed to appreciate the role of the firstborn.

As for Yitzchak's love of hunted meat, the Ramban says "that dignitaries and kings delight in this delicacy over all others. And regarding Yitzchak's request to Esav in particular that he should engage in the hunt, the Ramban remarks: "Esav would pander to his father by bringing him from the hunted food … and (Yitzchak) wanted to benefit from it so that it would enhance the closeness between them."

Yaakov left home without wealth so that he could escape quickly and so that he would not become a target for attack as he travelled the highways.

And as regards Yaakov's lack of clothing, the Ramban answers that Yaakov lacked nothing! But he borrowed Esav's clothing as they had the smell of the "field," the camouflage that Yaakov needed in order to carry off the subterfuge of the Blessings.

IN SUMMARY

This is certainly a tough debate to settle. No side wins easily. But if we can return to the basic principles, it is certainly fascinating that the Ramban refuses to see a Tzaddik who is blessed by God, experiencing financial difficulties. The Ramban needs to see a correlation between the spiritual and the material. For the Ibn Ezra, the two are absolutely disconnected. A wanderer like Eliyahu who is given lodgings by a random stranger for years on end[2] can be the holiest person. There is no symmetry between the material fate of the Man of God and his spiritual status; they are two disconnected realities.

What is the connection between the material and the spiritual? We experience the spirituality of Shabbat via material pleasure? Can there also be a correlation in other ways between material luxury and spiritual heights? On the other hand, wealth can at times be a distraction, a mode that takes a person far from the world of the spirit, to the world of indulgence and pleasure. Maybe the two are at odds with each other?

Shabbat Shalom!

[1] Each of the Avot are granted enormous respect by foreign Kings: Avraham with Malkitzedek and Avimelekh. Yitzchak and Avimelekh. Yaakov and Pharaoh.

[2] The woman from Tzrafat Melachim I 17:9,19-23.

Sderot, Qasaams and Fear

Qasaam missiles fall daily in Sderot. Last week one woman was killed. Yesterday, a man - a factory worker - was killed. Today, another 4 Qasaams. One fell near a school. I - like many Israelis - have been in emotional disengagement with the plight of Sderot. I have sort of distanced it emotionally and not allowed myself to connect. But this post really brought home the daily terror. Read it!

Don't Raise a Esav Like a Yaakov!

This passage by Rav Hirsch is very important for parents and educators alike. I will make some comments at the end.

Rav Hirsch's words are critical for successful parenting, and an important reminder for all educators. We cannot educate with one final product in minds. We have to look carefully at each of our children, each and every one of our talmidim, and spend time thinking about the way in which they may be stimulated, challenged supported, so that they may each reach their personal potential. So that each child can become a healthy, happy adult in the service of God and Nation. And this is easier said than done. It is mind-boggling to entertain the thought that with different educational approach, Esav might have become Esav Hatzaddik.

I vital point here is to look closely at our students and children and to identify emotions, character, and even warning signs, anger, distress. Rashi comments that in their childhood the children acted the same "and no one looked in an insightful way to understand their personalities." At age thirteen, they each went their separate ways. We have to look closely at our kids and to see their passions, their distresses, what excites them, what they struggle with. In this manner and only in this manner will we raise the next generation each in their own particular contribution to Judaism and the Jewish community. Only in this way will every child feel comfortable and excited by their Avodat Hashem.

A second point here which should not be understated in today's religious climate, is that Rav Hirsch understands that we need many different personality types, many professions and temperaments to make Am Yisrael. We are not supposed to all act/dress the same!

I imagine that in the 19th Century, in a world which had pre-designated ideas about class, occupation and social standing, Hirsch's thoughts were revolutionary and indeed desperately needed. Indeed, I feel that in many of today's educational environments, and in a world with post-modernist awareness, this message has been accepted and absorbed. We fully accept that each child needs unique challenges and care, and personal guidance. I do think however, that in today's world, there is also the opposite danger; that in an effort to assist each child develop their distinct talents and to maximise their potential, we can at times fall into the trap of overdoing it. We also need to teach children that there are times for conformity and community, that sometimes one simply needs to buckle to the system. The student or child is not always the centre of the universe. This also assists children in finding their place in the world.

ויגדלו הנערים - As long as they were little, no attention was paid to the slumbering differences in their natures (see on V.24), both had exactly the same teaching and educational treatment, and the great law of education חנוך לנער על פי דרכו "bring up each child in accordance with its own way" was forgotten: -That each child must be treated differently, with an eye to the slumbering tendencies of his nature, and out of them, be educated to develop his special characteristics for the one pure human and Jewish life. The great Jewish task in life is basically simple, one and the same for all, but in its realisation is as complicated and varied as human natures and tendencies are varied, and the manifold varieties of life that result from them.

When Father Jacob visualised the tribes of our nation in the sons standing around his death-bed, he saw, not only future priests and teachers, he saw around him the tribe of Levites, the tribes of royalty, of merchants, of farmers, of soldiers, before his mental eye he saw the nation in all its most manifold characteristics and diverse paths of life, and he blessed all of them… There, strength and courage, no less than brain and lofty thought and fine feelings are to have their representatives before God, and all, in the most varied ways of their callings are to achieve the one great common task of life.

But just because of that, must each one be brought up לפי דרכו according to the presumed path of life to which his tendencies lead, each one differently to the one great goal. To try to bring up a Jacob and an Esau in the same college, make them have the same habits and hobbies, want to teach and educate them in the same way for some studious, sedate, meditative life is the surest way to court disaster. A Jacob will, with ever increasing zeal and zest, imbibe knowledge from the well of wisdom and truth, while an Esau can hardly wait for the time when he can throw the old books, but at the same time, a whole purpose of life, behind his back, a life of which he has only learnt to know from one angle, and in a manner for which he can find no disposition in his whole nature.Had Isaac and Rebecca studied Esau's nature and character early enough, and asked themselves how can even an Esau, how can all the strength and energy, agility and courage that lies slumbering in this child be won over to be used in the service of God … then Jacob and Esau, with their totally different natures could still have remained twinbrothers in spirit and life; quite early in life Esau's "sword" and Jacob's "spirit" could have worked hand in hand, and who can say what a different aspect the whole history of the ages might have presented. But, as it was, ויגדלו הנערים, only when the boys had grown into men, one was surprised to see that, out of one and the selfsame womb, having had exactly the same care, training and schooling, two such contrasting persons emerge.

Rav Hirsch's words are critical for successful parenting, and an important reminder for all educators. We cannot educate with one final product in minds. We have to look carefully at each of our children, each and every one of our talmidim, and spend time thinking about the way in which they may be stimulated, challenged supported, so that they may each reach their personal potential. So that each child can become a healthy, happy adult in the service of God and Nation. And this is easier said than done. It is mind-boggling to entertain the thought that with different educational approach, Esav might have become Esav Hatzaddik.

I vital point here is to look closely at our students and children and to identify emotions, character, and even warning signs, anger, distress. Rashi comments that in their childhood the children acted the same "and no one looked in an insightful way to understand their personalities." At age thirteen, they each went their separate ways. We have to look closely at our kids and to see their passions, their distresses, what excites them, what they struggle with. In this manner and only in this manner will we raise the next generation each in their own particular contribution to Judaism and the Jewish community. Only in this way will every child feel comfortable and excited by their Avodat Hashem.

A second point here which should not be understated in today's religious climate, is that Rav Hirsch understands that we need many different personality types, many professions and temperaments to make Am Yisrael. We are not supposed to all act/dress the same!

I imagine that in the 19th Century, in a world which had pre-designated ideas about class, occupation and social standing, Hirsch's thoughts were revolutionary and indeed desperately needed. Indeed, I feel that in many of today's educational environments, and in a world with post-modernist awareness, this message has been accepted and absorbed. We fully accept that each child needs unique challenges and care, and personal guidance. I do think however, that in today's world, there is also the opposite danger; that in an effort to assist each child develop their distinct talents and to maximise their potential, we can at times fall into the trap of overdoing it. We also need to teach children that there are times for conformity and community, that sometimes one simply needs to buckle to the system. The student or child is not always the centre of the universe. This also assists children in finding their place in the world.

Tuesday, November 21, 2006

ipod shiur for Parashat Toldot.

I recorded an ipod shiur for the VBM for Parashat Toldot.

Access it here.

Access it here.

Sunday, November 19, 2006

Interview with Ravitzky

Prof. Aviezer Ravitzky - a leading religious zionist figure in Israel - was tragically run over by a bus some weeks ago in Jerusalem. He has still to regain consciousness. Notheless, Ynet today published an important interview that was conducted two weeks before the accident. It is certainly worthwhile reading (Hebrew).

Amongst it all, he says:

Amongst it all, he says:

"כידוע, רווחו בקרבנו שלוש תפיסות נבדלות באשר לפתרון המשבר בינינו לבין הפלסטינים: ארץ ישראל השלמה, הסדרי שלום, נסיגה חד- צדדית. יש מי שסבור שכולן נכשלו. אינני חושב כך. כל אחת הצליחה בחלקה ונכשלה בחלקה. אי-אפשר לומר שתפיסת ארץ ישראל השלמה נכשלה לחלוטין כאשר למעלה מ-200 אלף מתיישבים חיים ביהודה ושומרון; אי-אפשר לומר שתפיסת הסדרי השלום נכשלה לחלוטין כאשר יש הסכמים יציבים עם מצרים וירדן; אי-אפשר לומר שתפיסת ההתכנסות נכשלה כאשר היא טרם נוסתה. לכן גם ההצלחה וגם הכישלון היו קטועים. בעבר כמעט לכל אחד מאתנו הייתה עמדה מוצקה, כוללת, באשר לפתרון הרצוי, ואילו כיום רבים מאתנו רואים את הפגמים בעמדתם שלהם ואת החלקיות של כל פתרון. אנו אמביוולנטיים יותר. איננו יודעים בבירור אנה אנו הולכים".

אבל רביצקי סבור שאל לנו לחשוש. "טוב שהגענו לתודעה הזו", הוא אומר. "אנו נדרשים עתה לארגן את מחשבותינו מחדש, לשבור הגדרות דוֹגמטיות ולהיערך אחרת מבחינה רעיונית, מבחינה מדינית ומבחינה צבאית.

אבל רביצקי סבור שאל לנו לחשוש. "טוב שהגענו לתודעה הזו", הוא אומר. "אנו נדרשים עתה לארגן את מחשבותינו מחדש, לשבור הגדרות דוֹגמטיות ולהיערך אחרת מבחינה רעיונית, מבחינה מדינית ומבחינה צבאית.

Religion Is (Not) For Kids!

Rabbi Immanuel Jakobovitz z"l describes his thoughts upon a visit to a movie studio in Hollywood. This can be found in his book, "The Timely and the Timeless."

We had an introduction to one of the studios to view a film production. On calling to arrange our visit, I was asked if I had any young children with me, since that particular show included some ralher unchaste scenes and would not be suitable for children. I replied, if it is not fit for children, it cannot be fit for the parents either.

RELIGION AND MORALITY FOR JUVENILES

Does this not illustrate one of the most curious and perverted notions of our age? Religion and morality are for juveniles; Children must be protected from smutty literature, indecent pictures, imnmoral thoughts; they must not drink or gamble. But for grown-ups all this is in order, as if they were less sensual and more immune to corruption. What sort of a world are we going to have if goodness and decency were to be the exclusive preserve of children? What kind of an example are we going to set our children if we preach virtue for them and practise vice for ourselves?

The same goes for Judaism. Many people seem to think the Torah is a children's Torah. On Pesach they conduct a Seder not for themselves, but only for the sake of the children. They expect their children to go to Hebrew classes, but Jewish learning and reading is not for them.

Judaism teaches the reverse. Of course children must be trained in the virtues of religion and decency and learning to prepare themselves for the challenges of life ahead. But legally no obligations of any kind are incumbent on them until they reach Bar Mitzvah age-I 3 years for boys and 12 years for girls.

Judaism is an adult religion, meant primarily for grown-ups. With Jewish education often ending instead of beginning in earnest with Bar Mitzvah age, is it any wonder that so many Jews have such a juvenile, primitive notion of Judaism, that their understanding of Jewish thought - stunted before their brains matured - is of nursery or elementary school level, and therefore quite incompetent to cope with the complex intellectual challenges of our times? With such a childish appreciation of Jewish values, is it surprising that the flimsiest arguments or distractions encountered on the college campus are enough to knock down their Jewish loyalties and convictions like a pack of cards before the slightest breeze?

For holiness, just as for specially "holy" prayers like Kaddish and Kedushah, we require a quorum of adults, not children.

We had an introduction to one of the studios to view a film production. On calling to arrange our visit, I was asked if I had any young children with me, since that particular show included some ralher unchaste scenes and would not be suitable for children. I replied, if it is not fit for children, it cannot be fit for the parents either.

RELIGION AND MORALITY FOR JUVENILES

Does this not illustrate one of the most curious and perverted notions of our age? Religion and morality are for juveniles; Children must be protected from smutty literature, indecent pictures, imnmoral thoughts; they must not drink or gamble. But for grown-ups all this is in order, as if they were less sensual and more immune to corruption. What sort of a world are we going to have if goodness and decency were to be the exclusive preserve of children? What kind of an example are we going to set our children if we preach virtue for them and practise vice for ourselves?

The same goes for Judaism. Many people seem to think the Torah is a children's Torah. On Pesach they conduct a Seder not for themselves, but only for the sake of the children. They expect their children to go to Hebrew classes, but Jewish learning and reading is not for them.

Judaism teaches the reverse. Of course children must be trained in the virtues of religion and decency and learning to prepare themselves for the challenges of life ahead. But legally no obligations of any kind are incumbent on them until they reach Bar Mitzvah age-I 3 years for boys and 12 years for girls.

Judaism is an adult religion, meant primarily for grown-ups. With Jewish education often ending instead of beginning in earnest with Bar Mitzvah age, is it any wonder that so many Jews have such a juvenile, primitive notion of Judaism, that their understanding of Jewish thought - stunted before their brains matured - is of nursery or elementary school level, and therefore quite incompetent to cope with the complex intellectual challenges of our times? With such a childish appreciation of Jewish values, is it surprising that the flimsiest arguments or distractions encountered on the college campus are enough to knock down their Jewish loyalties and convictions like a pack of cards before the slightest breeze?

For holiness, just as for specially "holy" prayers like Kaddish and Kedushah, we require a quorum of adults, not children.

Tuesday, November 14, 2006

Tohar Neshek

Israel has always prided itself upon the value of Tohar Neshek – resort to violence only in accordance with a moral standard. Whereas Arab armies murdered prisoners-of-war, mutilated corpses and violated graves and Jewish Holy Places we decided that we – even in the throes of war – would act in an ethical manner.

This is from the TzaHaL website, from its moral code:

Human Life - The IDF servicemen and women will act in a judicious and safe manner in all they do, out of recognition of the supreme value of human life. During combat they will endanger themselves and their comrades only to the extent required to carry out their mission.

Purity of Arms - The IDF servicemen and women will use their weapons and force only for the purpose of their mission, only to the necessary extent and will maintain their humanity even during combat. IDF soldiers will not use their weapons and force to harm human beings who are not combatants or prisoners of war, and will do all in their power to avoid causing harm to their lives, bodies, dignity and property.

Having spoken to friends who are chayalim, they assure me that these values are still alive and well in TzaHaL and that the greatest care is taken not to harm human life, as long as the job gets done.

And yet, in the recent fighting, I have been disturbed by instances in which it would seem that really stupid decisions have been made, that have endangered human life. One example is the shelling of Beit Hanoun that killed 20 people last week. Why were these shells being used so close to civilian areas? And how can such a mistake be tolerated? Another is the widespread use of Cluster Bombs in Lebanon (that have killed many since the war.) I understand that they were necessary for the fighting, but was any consideration given to the aftermath of the war? (Maybe in war one musn't think about that. It is our them or us!) In today's Ha'aretz there was a report that claimed that Tzahal could have used a much safer weapon, an Israeli made cluster bomb that would never have produced all the civilian casualties that have happened since the war but that the army used a different type due to economic considerations.

Why? Is human life, Tohar Neshek, as alive in the IDF today as it once was? Or possibly, there always were "mistakes" and nothing has changed. Is this simply the price of war (and this is war)? Or have we become hardened and desensitized and lost our moral,human edge?

Some would say that the War on Terror is simply gruesomely complicated as militants live amongst civilians, function from within civilian centers and wear civilian clothes. It makes it impossible not to kill a serious number of civilians. I see this argument well. But has this really come up for public discussion here – in Knesset, in the media?

This war on terror is a battle that we are going to be fighting in Gaza and South Lebanon for the foreseeable future. We cannot afford to be immoral and callous. Worse would be that we simply cease to care. In the political dimension, many have framed the desire for Hitnatkut and Hitkansut as a wish to simply wash our hands of the entire problem. In the face of no options (no political nor military solution), we just walk out and leave them to their own problems. We have lost hope of a solution. However, we cannot lose sight of our own morality. Even if we wish that it would go away, our soldiers are fighting and we must know that we hold the moral high-ground.

Maybe Tohar Neshek is easy in the conventional battlefield. However, do we have an adequate moral "road-map" for this impossibly entangled web of militant and civilian, a civilian population that is totally mobilized to aid the terrorists; terrorists that seek to destroy Israel. (That is the case in Gaza for instance.) How DO we fight terror and keep our soul intact?

Tzarikh Iyun! We need this to be raised to the public debate. Not beacuse we are fearful about world pressure and world opinion when many Palestinians are killed in Beit Hanoun. (And yes. I do know that people from Beit Hanoun have been firing missiles daily at Israel... and nonetheless... we have to be moral.) We need it for ourselves, for our society! We need to know that our chayalim are acting in the most ethical manner despite the chaos of the Middle East. We need to make sure that when our politicians chant that "the IDF is the most moral army in the world," that these words have content and are not simply cliches.

This is from the TzaHaL website, from its moral code:

Human Life - The IDF servicemen and women will act in a judicious and safe manner in all they do, out of recognition of the supreme value of human life. During combat they will endanger themselves and their comrades only to the extent required to carry out their mission.

Purity of Arms - The IDF servicemen and women will use their weapons and force only for the purpose of their mission, only to the necessary extent and will maintain their humanity even during combat. IDF soldiers will not use their weapons and force to harm human beings who are not combatants or prisoners of war, and will do all in their power to avoid causing harm to their lives, bodies, dignity and property.

Having spoken to friends who are chayalim, they assure me that these values are still alive and well in TzaHaL and that the greatest care is taken not to harm human life, as long as the job gets done.

And yet, in the recent fighting, I have been disturbed by instances in which it would seem that really stupid decisions have been made, that have endangered human life. One example is the shelling of Beit Hanoun that killed 20 people last week. Why were these shells being used so close to civilian areas? And how can such a mistake be tolerated? Another is the widespread use of Cluster Bombs in Lebanon (that have killed many since the war.) I understand that they were necessary for the fighting, but was any consideration given to the aftermath of the war? (Maybe in war one musn't think about that. It is our them or us!) In today's Ha'aretz there was a report that claimed that Tzahal could have used a much safer weapon, an Israeli made cluster bomb that would never have produced all the civilian casualties that have happened since the war but that the army used a different type due to economic considerations.

Why? Is human life, Tohar Neshek, as alive in the IDF today as it once was? Or possibly, there always were "mistakes" and nothing has changed. Is this simply the price of war (and this is war)? Or have we become hardened and desensitized and lost our moral,human edge?

Some would say that the War on Terror is simply gruesomely complicated as militants live amongst civilians, function from within civilian centers and wear civilian clothes. It makes it impossible not to kill a serious number of civilians. I see this argument well. But has this really come up for public discussion here – in Knesset, in the media?

This war on terror is a battle that we are going to be fighting in Gaza and South Lebanon for the foreseeable future. We cannot afford to be immoral and callous. Worse would be that we simply cease to care. In the political dimension, many have framed the desire for Hitnatkut and Hitkansut as a wish to simply wash our hands of the entire problem. In the face of no options (no political nor military solution), we just walk out and leave them to their own problems. We have lost hope of a solution. However, we cannot lose sight of our own morality. Even if we wish that it would go away, our soldiers are fighting and we must know that we hold the moral high-ground.

Maybe Tohar Neshek is easy in the conventional battlefield. However, do we have an adequate moral "road-map" for this impossibly entangled web of militant and civilian, a civilian population that is totally mobilized to aid the terrorists; terrorists that seek to destroy Israel. (That is the case in Gaza for instance.) How DO we fight terror and keep our soul intact?

Tzarikh Iyun! We need this to be raised to the public debate. Not beacuse we are fearful about world pressure and world opinion when many Palestinians are killed in Beit Hanoun. (And yes. I do know that people from Beit Hanoun have been firing missiles daily at Israel... and nonetheless... we have to be moral.) We need it for ourselves, for our society! We need to know that our chayalim are acting in the most ethical manner despite the chaos of the Middle East. We need to make sure that when our politicians chant that "the IDF is the most moral army in the world," that these words have content and are not simply cliches.

Sunday, November 12, 2006

Was Rivka Three Years Old?

We have all learned the Rashi that states that Rivka was three when she married a 37 year old Yitzchak! This has always bothered me. I can think of a few reasons:

1. Because the actions of Rivka in ch.24 - the sheer volume of water that she shleps, her parents consulting with her - are not possible for a three year old. (And please - don't tell me that human nature has changed or that she was such a tzadeket etc. etc.)

2. Because the Akeida doesn't seem to happen to a 37-year-old.

3. Because it is simply wierd for anyone to marry a 3 year old, let alone an middle aged bachelor. And we treat Rivka as a serious adult from the start.

The basis of this timeframe comes from Seder Olam (a very old Tannaitic work) which links three parshiot: The Akeida - Avraham hearing about Rivka's birth - and Sara's death. And assumes that they take place at the same time since they are mentioned concurrently. Hence, Sarah dies at age 127 which puts him at 37 at the time of the Akeida (when Rivka was born) and since Bereshit 25:20 states that he married at age 40, Rivka must have been 3 years old!

The easier solution would be to simply suggest that the Akeida is not linked to Sarah's death and happened maybe 20-30 years prior to her death. (See Ibn Ezra 22:4 and Ramban on 23:2.) Hence Yitzchak is 10-15 years old at the Akeida; and Rivka is at a regular marriagable age when Yitzchak marries her.

See this excellent shiur which discusses this in detail.

1. Because the actions of Rivka in ch.24 - the sheer volume of water that she shleps, her parents consulting with her - are not possible for a three year old. (And please - don't tell me that human nature has changed or that she was such a tzadeket etc. etc.)

2. Because the Akeida doesn't seem to happen to a 37-year-old.

3. Because it is simply wierd for anyone to marry a 3 year old, let alone an middle aged bachelor. And we treat Rivka as a serious adult from the start.

The basis of this timeframe comes from Seder Olam (a very old Tannaitic work) which links three parshiot: The Akeida - Avraham hearing about Rivka's birth - and Sara's death. And assumes that they take place at the same time since they are mentioned concurrently. Hence, Sarah dies at age 127 which puts him at 37 at the time of the Akeida (when Rivka was born) and since Bereshit 25:20 states that he married at age 40, Rivka must have been 3 years old!

The easier solution would be to simply suggest that the Akeida is not linked to Sarah's death and happened maybe 20-30 years prior to her death. (See Ibn Ezra 22:4 and Ramban on 23:2.) Hence Yitzchak is 10-15 years old at the Akeida; and Rivka is at a regular marriagable age when Yitzchak marries her.

See this excellent shiur which discusses this in detail.

Friday, November 10, 2006

A Song for Shabbat

Jewish music is frequently so boring, so predictable and stale. Much of the creativity, both musicala and lyrical that one finds in secular music is quite often missing from the Jewish music world.

Some years back, I came across the music of Aaron Razel and I just loved it. He is an excellent musician, a beautiful Jew, he learns Torah, sings and composes with creativity, love, passion. I have seen him in concert and he is just great. His divrei Torah and his sweetness combine with his music. In our house, my kids know all his songs as we play his CD's all the time.

One song of his is pertinent to this weeks parsha. He sings what might seem like a strange passuk to put to song. It is from the akeida: הנה האש והעצים ואיה השה לעולה asks Yitzchak. Avraham answers אלוקים יראה לו השה לעולה בני. The final word בני can be read directly as if avraham is addressing Yitzchak, or possibly, with a pause, as if to say: You, my son are that Korban.

Well Aaron Razel sings this song and he repeats the word בני over and over, again and again. I have no clue whether he intended this but it so reminds me of the anguish of David Hamelech for his son as he is tortured by the loss of his son and is inconsolable as he repeats over and over:

בני אבשלום בני בני אבשלום (שמו"ב י"ט: א)

In other words, I hear David's anguish transferred to Avraham as he contemplates the prospective death of his son.

In addition, Aaron Razel includes a fantastic piano solo/improvisation interlude which just reinforces for me the feeling of Avrahams doubts and fears, second-thoughts and osciallations.

In my mind, there is much more to this song, but you'll have to listen to the whole thing and draw your own conclusions.

This website has a bit of the song (Fire and Wood) but it's a great album with some beautiful songs. Worthwhile!

Some years back, I came across the music of Aaron Razel and I just loved it. He is an excellent musician, a beautiful Jew, he learns Torah, sings and composes with creativity, love, passion. I have seen him in concert and he is just great. His divrei Torah and his sweetness combine with his music. In our house, my kids know all his songs as we play his CD's all the time.

One song of his is pertinent to this weeks parsha. He sings what might seem like a strange passuk to put to song. It is from the akeida: הנה האש והעצים ואיה השה לעולה asks Yitzchak. Avraham answers אלוקים יראה לו השה לעולה בני. The final word בני can be read directly as if avraham is addressing Yitzchak, or possibly, with a pause, as if to say: You, my son are that Korban.

Well Aaron Razel sings this song and he repeats the word בני over and over, again and again. I have no clue whether he intended this but it so reminds me of the anguish of David Hamelech for his son as he is tortured by the loss of his son and is inconsolable as he repeats over and over:

בני אבשלום בני בני אבשלום (שמו"ב י"ט: א)

In other words, I hear David's anguish transferred to Avraham as he contemplates the prospective death of his son.

In addition, Aaron Razel includes a fantastic piano solo/improvisation interlude which just reinforces for me the feeling of Avrahams doubts and fears, second-thoughts and osciallations.

In my mind, there is much more to this song, but you'll have to listen to the whole thing and draw your own conclusions.

This website has a bit of the song (Fire and Wood) but it's a great album with some beautiful songs. Worthwhile!

Thursday, November 09, 2006

Parashat Vayera - Abraham's Vision

The Parasha opens with Avraham experiencing a vision of God. Suddenly his attention is diverted to three strangers walking by and he simply abandons God in order to receive some guests. Avraham might be a champion of Hachnasat Orchim, but he didn't even give God a chance to speak!

In our shiur this week, we examine the opening Parsha and we shall see THREE very different ways of reading and imagining the text. At the end we ask about the significance of it all.

Read the shiur here.

In our shiur this week, we examine the opening Parsha and we shall see THREE very different ways of reading and imagining the text. At the end we ask about the significance of it all.

Read the shiur here.

Wednesday, November 08, 2006

The Separation Fence

This post is going to be controversial. Some of you are probably not going to like it. Just for the record, I am a Zionist. I support Israel's right to self-defense. I live in Israel and have done for 15 years now. I am raising 4 children here with a love of the land, its heritage, its people and its language. I live in Gush Etzion. If you don't know where that is, it is in the West Bank, 15 minutes from Jerusalem, 8 minutes from the southern suburbs of Beit Lechem - Bethlehem. And I guess that makes me a "settler." I also believe that Palestinians are people, and that they should be able to live in dignity. OK now!.

Every day, I drive to Jerusalem and pass the extensive work that is being done in constructing the security wall. Yes. I am aware there is controversy about the very name: a fence, a barrier, a wall. And then there is the adjective that describes the fence, wall or barrier. It ranges from the term: security, to "defense," "separation," "apartheid," and probably there are others. For some perspective from the Israeli Government Here is the official take on the Fence.

Here are some pictures, scenes I shot on my way to work a week or two ago.

Let me tell you. The construction and mainly preparation work (levelling the earth and preparing the route of the wall) has been going on for six months now. Many trucks and tractors daily toil all day changing the contours of the countryside in order to construct this barrier. By the looks of it, it will be a monstrous thing. Apparently much of the barrier is a fence, but in places in which there are concerns that the road may be a target for shooting, it becomes a concrete wall.

Let me tell you. The construction and mainly preparation work (levelling the earth and preparing the route of the wall) has been going on for six months now. Many trucks and tractors daily toil all day changing the contours of the countryside in order to construct this barrier. By the looks of it, it will be a monstrous thing. Apparently much of the barrier is a fence, but in places in which there are concerns that the road may be a target for shooting, it becomes a concrete wall.

Well, in short, I hate this wall. I think it is a bad idea, and it will have even worse effects in the future. This post is to explain why.

1. I don't think it is effective in stopping terror. In Gush Katif/Gaza underground tunnels that avoid the border fence stretch for many hundreds of metres. The tunnel used in the operation to capture Gilad Shalit was almost a kilometer long. Even in the West Bank where the soil is not sandy, terrorists will be able to circumvent the wall.

In addition. Thank God, we have had very few suicide attacks lately, even though we know that the terrorists are trying all the time. Many of those who DO get through are transported by Israeli's ferrying illegal Palestinian labour; Israelis who make a quick buck on the black market. Will the fence stop this? And if Tzahal have been successful thus far, without a fence, then will a physical barrier make a considerable difference?

2. Until the summer, there were thoughts and plans of a disengagement – a Hitkansut – in the West Bank. Even though no one would admit it, the separation fence was supposed to be a quasi-border. But now that for everyone the withdrawal on the West Bank is far off the horizon, does this border fence make any sense?

3. This issue relates also to the route of the Fence. For legal reasons, in many places the fence must follow pretty much the Green Line. Now take, for example the northern Jordan Valley. One travels through the Jordan Valley and there is little hityashvut, but most of it is Jewish. By erecting the Fence on the Green Line, they have excluded a heroic halutzic settlement like Shadmot Mehola and placed in on the "Palestinian" side! Why? There are no Palestinians there! It is not security! It is politics. We are effectively withdrawing from land voluntarily and setting our own pioneers apart from the Israeli "mainland". What an insult to these people who have battled for years to establish their farms and communities!

And for those on the Right Wing, are they really interested in effectively creating a wider exclusively Palestinian region? Effectively we are creating far larger areas which are "de facto" Palestine. Why?

4. From the Palestinian perspective, I do have to say that if I was a Palestinian and they built that wall in my back yard, I would sign up with Hamas tomorrow. It is so imposing, so grey, so immense, so restricting. It feels like a big prison. I feel that way as I pass the construction on the way to Jerusalem and also on the way to Beit Shemesh. Gush Etzion will be a walled enclave, and I feel like they are walling me in! Think about what a Palestinian kid feels like. It is not a ghetto – people and trade can get through - but it looks too much like one. I cannot but feel that this wall is creating problems, big problems rather than solving them. Moreover, we hear about the suffering and inconvenience it is causing the Palestinian population. For many, this is genuine hardship.

5. And then there is the hills and valleys themselves - nature. I have to say that the strenth of my feelings on this startled even me! I am far from being a child of the '70's flower power. And yet, the ripping apart of hills, the destruction of fertile land, the obstruction of views, the ruining of natural beautiful countryside is something which has disturbed me in a very deep place. It seems like we are violating the landscape itself! And in Gush Etzion we used to see deer running freely through the hills. Will they be able to run, or will they also be trapped by the separation wall? We are scarring the landscape, making a permanent indelible mark on wide tracts of our historic beautiful land. Have we considered this aspect?

6. And there is the expense. Such enormous resources are being piled into this project! Just the half mile stretch that I witness being constructed daily has taken at least ten trucks half year to work on and they are still not yet finished! Not millions, but billions! I shudder to think of the welfare programs the education, the charity, the health causes that could be funded by those monies!

I would even suggest that Israel's long-term security would be stronger if all those billions were invested in Zionist education programs for Israelis strengthening their understanding of our right to our land and the nature of our struggle with the Arabs and the Palestinians.

What a waste! Whoever came up with such a megalomaniac plan to build a Great Wall of China through the delicate countryside of our tiny land was not thinking straight. Maybe in Ramat Aviv and Herzlia it sounds sensible to build a wall to keep terrorists out. Maybe if you are certain that you are going to more or less '67 borders it mmakes sense. For me I don't get it. The negatives far outway the positives to me.

Every day, I drive to Jerusalem and pass the extensive work that is being done in constructing the security wall. Yes. I am aware there is controversy about the very name: a fence, a barrier, a wall. And then there is the adjective that describes the fence, wall or barrier. It ranges from the term: security, to "defense," "separation," "apartheid," and probably there are others. For some perspective from the Israeli Government Here is the official take on the Fence.

Here are some pictures, scenes I shot on my way to work a week or two ago.

Let me tell you. The construction and mainly preparation work (levelling the earth and preparing the route of the wall) has been going on for six months now. Many trucks and tractors daily toil all day changing the contours of the countryside in order to construct this barrier. By the looks of it, it will be a monstrous thing. Apparently much of the barrier is a fence, but in places in which there are concerns that the road may be a target for shooting, it becomes a concrete wall.

Let me tell you. The construction and mainly preparation work (levelling the earth and preparing the route of the wall) has been going on for six months now. Many trucks and tractors daily toil all day changing the contours of the countryside in order to construct this barrier. By the looks of it, it will be a monstrous thing. Apparently much of the barrier is a fence, but in places in which there are concerns that the road may be a target for shooting, it becomes a concrete wall.Well, in short, I hate this wall. I think it is a bad idea, and it will have even worse effects in the future. This post is to explain why.

1. I don't think it is effective in stopping terror. In Gush Katif/Gaza underground tunnels that avoid the border fence stretch for many hundreds of metres. The tunnel used in the operation to capture Gilad Shalit was almost a kilometer long. Even in the West Bank where the soil is not sandy, terrorists will be able to circumvent the wall.

In addition. Thank God, we have had very few suicide attacks lately, even though we know that the terrorists are trying all the time. Many of those who DO get through are transported by Israeli's ferrying illegal Palestinian labour; Israelis who make a quick buck on the black market. Will the fence stop this? And if Tzahal have been successful thus far, without a fence, then will a physical barrier make a considerable difference?

2. Until the summer, there were thoughts and plans of a disengagement – a Hitkansut – in the West Bank. Even though no one would admit it, the separation fence was supposed to be a quasi-border. But now that for everyone the withdrawal on the West Bank is far off the horizon, does this border fence make any sense?

3. This issue relates also to the route of the Fence. For legal reasons, in many places the fence must follow pretty much the Green Line. Now take, for example the northern Jordan Valley. One travels through the Jordan Valley and there is little hityashvut, but most of it is Jewish. By erecting the Fence on the Green Line, they have excluded a heroic halutzic settlement like Shadmot Mehola and placed in on the "Palestinian" side! Why? There are no Palestinians there! It is not security! It is politics. We are effectively withdrawing from land voluntarily and setting our own pioneers apart from the Israeli "mainland". What an insult to these people who have battled for years to establish their farms and communities!

And for those on the Right Wing, are they really interested in effectively creating a wider exclusively Palestinian region? Effectively we are creating far larger areas which are "de facto" Palestine. Why?

4. From the Palestinian perspective, I do have to say that if I was a Palestinian and they built that wall in my back yard, I would sign up with Hamas tomorrow. It is so imposing, so grey, so immense, so restricting. It feels like a big prison. I feel that way as I pass the construction on the way to Jerusalem and also on the way to Beit Shemesh. Gush Etzion will be a walled enclave, and I feel like they are walling me in! Think about what a Palestinian kid feels like. It is not a ghetto – people and trade can get through - but it looks too much like one. I cannot but feel that this wall is creating problems, big problems rather than solving them. Moreover, we hear about the suffering and inconvenience it is causing the Palestinian population. For many, this is genuine hardship.

5. And then there is the hills and valleys themselves - nature. I have to say that the strenth of my feelings on this startled even me! I am far from being a child of the '70's flower power. And yet, the ripping apart of hills, the destruction of fertile land, the obstruction of views, the ruining of natural beautiful countryside is something which has disturbed me in a very deep place. It seems like we are violating the landscape itself! And in Gush Etzion we used to see deer running freely through the hills. Will they be able to run, or will they also be trapped by the separation wall? We are scarring the landscape, making a permanent indelible mark on wide tracts of our historic beautiful land. Have we considered this aspect?

6. And there is the expense. Such enormous resources are being piled into this project! Just the half mile stretch that I witness being constructed daily has taken at least ten trucks half year to work on and they are still not yet finished! Not millions, but billions! I shudder to think of the welfare programs the education, the charity, the health causes that could be funded by those monies!

I would even suggest that Israel's long-term security would be stronger if all those billions were invested in Zionist education programs for Israelis strengthening their understanding of our right to our land and the nature of our struggle with the Arabs and the Palestinians.

What a waste! Whoever came up with such a megalomaniac plan to build a Great Wall of China through the delicate countryside of our tiny land was not thinking straight. Maybe in Ramat Aviv and Herzlia it sounds sensible to build a wall to keep terrorists out. Maybe if you are certain that you are going to more or less '67 borders it mmakes sense. For me I don't get it. The negatives far outway the positives to me.

Sunday, November 05, 2006

Saturday, November 04, 2006

The Gay Pride Parade and Haredi Violence

We are now witnessing the fourth night of Haredi riots in Jerusalem in anticipation of the Gay Pride Parade this week in Jerusalem. The popular opinion is that the Haredim are trying to stop the parade by force. That if they show how much violence the parade sparks, that the police will decide that they cannot control the parade and will call the entire thing off. (Ynet has a video here.)

I am extremely worried about this situation, and here are some points to think about:

1. There has been talk about people getting killed at the Parade if it goes ahead. Last time, a couple of people were stabbed by a protester. Now, we have 4 days of violence. Where is the justification to threaten innocent people, to attack police, to burn public property, in our tradition?

2. I am against any violence that aims to threaten the public order to the degree that the forces of law buckle and give in. I felt that with demonstrations against the disengagement and I feel it here. One can demonstrate , but legally. The Haredi demonstration some years ago against the Supreme Court was legal , massive and influential. Force of Law here in Israel is weak enough and unfortunately weakening by the day. How can a legal march be cancelled because people threaten it? We cannot – as a society - allow violence to dictate our national life. If we do, then איש את ראהו חיים בלעו. It will be a terrible precedent if public violence wins the day. (I say this on the weekend when Rabin's assassination is being commemorated. Another instance where we suffered from the attitude that violent unlawful actions can alter the course of the nation. And precisely that should be a warning for us.)

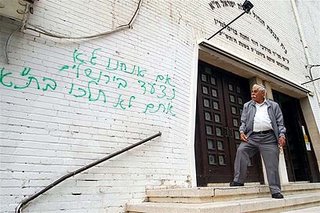

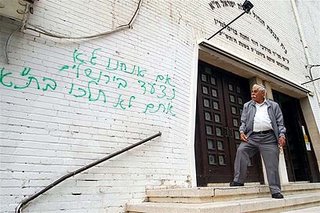

3. Another worrying phenomenon is that this violence is now pushing the issue of Religious-liberal tensions back into the public arena and also the tension between Jerusalem and Tel Aviv. See this picture of graffiti from a Tel Aviv shul this week. (The Graffitti says: If we won't march in Jerusalem, then you will not be able to walk through Tel Aviv.)

It has been quite a while since there was a flare of Haredi-Secular tension. It has ONLY bad side-effects. There are ways to solve things in more peaceable and harmonious manner. (Unless people have an interest in there being violence?)

4. On the other hand, I do feel that the Open House who organise the Jerusalem march are creating an unnecessary provocation. (Maybe this is part of the problem. Some people are interested in having things escalate and hit the headlines!) Every year there is a large Gay parade in Tel Aviv. As this article in Jpost states, life for Gays in Jerusalem is good. But Jerusalem is predominantly a religious city (Jews, Moslems and Christians.) Is there a need to take the Gay issue and "in your face" everyone with it? That is the same reason that in general I am not enthusiastic of Gay parades. I don't like taking our sexuality (Homo or Hetro) into the public arena. And in Jerusalem it seems way over the edge. The Open House have an agenda to push Homosexuality into the mainstream. Most Jerusalemites want to live and let live but they do not welcome this.

5. And again in the balancing act, we don't need an a anti-Gay backlash. Even from a Torah perspective. Obviously, the Torah precludes Homosexuality. At the same time, many people feel an innate desire to engage in Homosexual behaviour. Yes; From a Torah perspective we are against Homosexuality and that is clear. At teh same time we can sympathise with the difficulties and personal emotional torment of a religious individual who is suffering as a result of his struggle with his Homosexual inclinations. All of this is besides the point of this discussion. That can all hold without the parade and without the violence (or with the parade and no violence!) ( Having said that, I do note some irony in the fact that this is all happening on the week of Parashat Vayera with its depiction of Sedom and its destruction. A few weeks back when the topic of the Parade came up in Knesset, one of the Arab MK's said: Why do they have to march in Jerusalem; They should march in Sedom!)

Let's hope that somehow it will end well. I feel somehow pessimistic.

I am extremely worried about this situation, and here are some points to think about:

1. There has been talk about people getting killed at the Parade if it goes ahead. Last time, a couple of people were stabbed by a protester. Now, we have 4 days of violence. Where is the justification to threaten innocent people, to attack police, to burn public property, in our tradition?

2. I am against any violence that aims to threaten the public order to the degree that the forces of law buckle and give in. I felt that with demonstrations against the disengagement and I feel it here. One can demonstrate , but legally. The Haredi demonstration some years ago against the Supreme Court was legal , massive and influential. Force of Law here in Israel is weak enough and unfortunately weakening by the day. How can a legal march be cancelled because people threaten it? We cannot – as a society - allow violence to dictate our national life. If we do, then איש את ראהו חיים בלעו. It will be a terrible precedent if public violence wins the day. (I say this on the weekend when Rabin's assassination is being commemorated. Another instance where we suffered from the attitude that violent unlawful actions can alter the course of the nation. And precisely that should be a warning for us.)

3. Another worrying phenomenon is that this violence is now pushing the issue of Religious-liberal tensions back into the public arena and also the tension between Jerusalem and Tel Aviv. See this picture of graffiti from a Tel Aviv shul this week. (The Graffitti says: If we won't march in Jerusalem, then you will not be able to walk through Tel Aviv.)

It has been quite a while since there was a flare of Haredi-Secular tension. It has ONLY bad side-effects. There are ways to solve things in more peaceable and harmonious manner. (Unless people have an interest in there being violence?)

4. On the other hand, I do feel that the Open House who organise the Jerusalem march are creating an unnecessary provocation. (Maybe this is part of the problem. Some people are interested in having things escalate and hit the headlines!) Every year there is a large Gay parade in Tel Aviv. As this article in Jpost states, life for Gays in Jerusalem is good. But Jerusalem is predominantly a religious city (Jews, Moslems and Christians.) Is there a need to take the Gay issue and "in your face" everyone with it? That is the same reason that in general I am not enthusiastic of Gay parades. I don't like taking our sexuality (Homo or Hetro) into the public arena. And in Jerusalem it seems way over the edge. The Open House have an agenda to push Homosexuality into the mainstream. Most Jerusalemites want to live and let live but they do not welcome this.

5. And again in the balancing act, we don't need an a anti-Gay backlash. Even from a Torah perspective. Obviously, the Torah precludes Homosexuality. At the same time, many people feel an innate desire to engage in Homosexual behaviour. Yes; From a Torah perspective we are against Homosexuality and that is clear. At teh same time we can sympathise with the difficulties and personal emotional torment of a religious individual who is suffering as a result of his struggle with his Homosexual inclinations. All of this is besides the point of this discussion. That can all hold without the parade and without the violence (or with the parade and no violence!) ( Having said that, I do note some irony in the fact that this is all happening on the week of Parashat Vayera with its depiction of Sedom and its destruction. A few weeks back when the topic of the Parade came up in Knesset, one of the Arab MK's said: Why do they have to march in Jerusalem; They should march in Sedom!)

Let's hope that somehow it will end well. I feel somehow pessimistic.

Thursday, November 02, 2006

Lech Lecha - The Intimate Relationship

Our Parsha opens with a colossal vacuum, a bewildering omission. God speaks to the elderly Avraham (he is 75 years old) commanding him to follow him to a new undesignated land in order to found a new nation. But we know nothing of his personal past. We all want to know: Why Abraham? What make Abraham "The One?" How did he gain this unique position in History? What act made him worthy, what virtue made him the chosen one? And why does the Torah deny us this information? Of all the personalities in the Torah, we generally receive some background to their persona. With Avraham we have a total blackout. If his history is so important, so exciting and rich, then why are we denied this history?

"Abraham, the great knight of faith, according to tradition searched and discovered God in the star-lit heavens of Mesopotamia. Yet, he felt an intense loneliness and could not find solace in the silent companionship of God whose image was reflected in the boundless stretches of the cosmos. Only when he met God on earth as Father, Brother and Friend – not only on the uncharted astral routes – did he feel redeemed. Our sages said that before Abraham appeared majestas dei was reflected only by the distant heavens and it was a mute nature which "spoke" of the glory of God. It was Abraham who "crowned" Him as the God of the earth i.e. the God of men." (Lonely Man of Faith –Tradition edition pg.32)

In this wonderful piece by Rav Soloveitchik, we read of two dimensions of the God-man experience. One can perceive of God in intellectual terms. That gives you a certain perception of God, but it is distant and impersonal. Rav Soloveitchik talks of the "Covenantal man of faith" as "craving for a personal and intimate relation with God." There is a dimension of the man-God interaction that rests in the realm of experience, not cognition, of two-way relationship, rather than independent contemplation and thought. In Parashat Lech Lecha Abraham shares an intimate relationship with God, as we see God's care and worry for Avraham as he listens to Avraham's worries and concerns and reassures him with a gentle: "Do not fear Avram, I will protect you[1]." Where in our parsha Avraham is told, "Walk before me in perfection and I will make a covenant between Myself and you[2]." Avraham and God from the first moment of "Lech Lecha" walk together! It is a living breathing interactive relationship with God.

When does God emerge from the shadows? At what moment does God begin to build this mode of relationship with Avraham? I would think that it is the moment that God actually addresses Avraham, when Avraham begins to act together with God, responding to His call, interacting with Him. In this perspective then, the command of "Lech Lecha" is THE watershed moment in which God transformed from being distant to close, from anonymity to familiarity. It is the critical beginning of the relationship. That moment of "Lech Lecha" is the start of the living experience of God.

For Rav Soloveitchik we are uninterested in the story prior to the great moment of God's revelation to Avraham. Why transcribe the perception of the anonymous remote distant God? We begin Abraham's history at the moment that he experiences the true God relationship; the intimacy of God. That is the beginning of the story.

Shabbat Shalom!

READ the entire shiur here

[1] 15:1 and see also in 13:14 where God would appear to come to reassure Avraahm and console him "after Lot departed from him."

[2] 17:1-2

"Abraham, the great knight of faith, according to tradition searched and discovered God in the star-lit heavens of Mesopotamia. Yet, he felt an intense loneliness and could not find solace in the silent companionship of God whose image was reflected in the boundless stretches of the cosmos. Only when he met God on earth as Father, Brother and Friend – not only on the uncharted astral routes – did he feel redeemed. Our sages said that before Abraham appeared majestas dei was reflected only by the distant heavens and it was a mute nature which "spoke" of the glory of God. It was Abraham who "crowned" Him as the God of the earth i.e. the God of men." (Lonely Man of Faith –Tradition edition pg.32)

In this wonderful piece by Rav Soloveitchik, we read of two dimensions of the God-man experience. One can perceive of God in intellectual terms. That gives you a certain perception of God, but it is distant and impersonal. Rav Soloveitchik talks of the "Covenantal man of faith" as "craving for a personal and intimate relation with God." There is a dimension of the man-God interaction that rests in the realm of experience, not cognition, of two-way relationship, rather than independent contemplation and thought. In Parashat Lech Lecha Abraham shares an intimate relationship with God, as we see God's care and worry for Avraham as he listens to Avraham's worries and concerns and reassures him with a gentle: "Do not fear Avram, I will protect you[1]." Where in our parsha Avraham is told, "Walk before me in perfection and I will make a covenant between Myself and you[2]." Avraham and God from the first moment of "Lech Lecha" walk together! It is a living breathing interactive relationship with God.

When does God emerge from the shadows? At what moment does God begin to build this mode of relationship with Avraham? I would think that it is the moment that God actually addresses Avraham, when Avraham begins to act together with God, responding to His call, interacting with Him. In this perspective then, the command of "Lech Lecha" is THE watershed moment in which God transformed from being distant to close, from anonymity to familiarity. It is the critical beginning of the relationship. That moment of "Lech Lecha" is the start of the living experience of God.

For Rav Soloveitchik we are uninterested in the story prior to the great moment of God's revelation to Avraham. Why transcribe the perception of the anonymous remote distant God? We begin Abraham's history at the moment that he experiences the true God relationship; the intimacy of God. That is the beginning of the story.

Shabbat Shalom!

READ the entire shiur here

[1] 15:1 and see also in 13:14 where God would appear to come to reassure Avraahm and console him "after Lot departed from him."

[2] 17:1-2

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)